The Albanese government’s failure to conclude security treaties with Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu shows the hollowness of Australian foreign policy in the Pacific.

Not finalising these deals is the result of insufficient diplomatic engagement, a lack of genuine local interest and a breakdown of what our diplomats like to call statecraft.

Frankly, Beijing plays a faster and more ruthless ground game. We can confidently assume the Chinese Communist Party was working behind the scenes to undermine Australia’s plan with Vanuatu and PNG leaders.

This week Anthony Albanese was left signing a “joint communique” in Port Moresby. Something had to happen to satisfy the cameras, but it was a hollow outcome. How seriously should the so-called Pukpuk Treaty be taken if the PNG cabinet can’t even bring itself to endorse it?

What makes the ANZUS Treaty work so effectively between Australia and the US is the shared drive, based on mutual interest, for practical defence co-operation. Australia and Britain have sustained a deep defence and intelligence relationship on the basis of no treaty-level agreements at all.

The Albanese-Marape joint communique reports the “core principles” of the Pukpuk Treaty. It is described as “a mutual defence Alliance which recognises that an armed attack on Australia or Papua New Guinea would be a danger to the peace and security of both countries”.

This echoes article four of the ANZUS Treaty, which says “an armed attack in the Pacific area on any of the parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety”.

But the ANZUS Treaty goes on to say each signatory “would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes”.

We do not know what the operative language is in the Pukpuk Treaty. What would Port Moresby and Canberra be expected to do in the event of a threat to the other’s security?

What is really being discussed here is how Canberra can persuade PNG to deny China influence in Port Moresby and remain reliably engaged with Australia on defence and security. That’s a critical Australian strategic objective and fundamentally in PNG’s interest, too.

For whatever reason it seems that members of PNG Prime Minister James Marape’s cabinet were not persuaded. Perhaps there were concerns that this was undermining PNG’s sovereignty.

We clearly needed a more adroit diplomatic effort to make the case for dealing with Australia in preference to Chinese “money diplomacy”. The price we must pay is a willingness to rebuild the PNG Defence Force and to ensure that Port Moresby always sees Australia as its chief security partner.

With fewer than 4000 people, the PNGDF is in a distressed state. At Murray Barracks in Port Moresby one can see a large number of men in uniform long past retirement age. The absence of a pension system for soldiers keeps them in service way too long.

As Marape said at the press conference with the Prime Minister, “I have no ability to defend this country.” If Australia is seriously planning to provide a defence capability for PNG, the Australian Defence Force must start operating in PNG to a far greater extent than it is now.

Unfortunately, the ADF has resisted all past attempts to establish a meaningful presence in PNG, for example at the Lombrum naval base on Manus Island.

In November 2018 Scott Morrison announced that Lombrum naval base would operate as a joint ADF-PNGDF facility. This has not happened.

In August this year Defence Minister Richard Marles revealed the cost of modernising Lombrum had doubled to more than $500m, more than double the entire PNG defence budget. Even with this investment the wharf is not large enough to accommodate Australian naval vessels.

Albanese should propose developing a rotational ADF presence in PNG, on the lines of the US Marine Corps presence in Darwin.

Military engagement is sustained by a real presence of military forces regularly working with local counterparts. Australia walked away from that kind of regional engagement at about the time PNG got its independence.

Such a defence footprint creates a believable basis for a treaty. It will be costly, but not as costly as ceding strategic influence to China in our near neighbourhood.

The Pukpuk Treaty declares a “shared ambition to establish a recruitment pathway for Papua New Guinea citizens into the Australian Defence Force”. Albanese would be better off developing strategies to get Australians into the ADF. Other than for perhaps a handful of people in light infantry roles I see little scope for a PNG recruitment scheme to work.

Australian commentators rightly judge that the prime source of threat is the People’s Republic of China. Historically, though, PNG has faced other security concerns.

What role would the Pukpuk Treaty play if, for example, there was a return of cross-border incidents along the 800km land border between Indonesia and PNG?

What role would the Pukpuk Treaty play if the PNGDF finds itself fighting another bloody insurgency conflict with independence forces on the island of Bougainville? In the 1980s and 90s, conflict on Bougainville cost 10,000 lives.

Future Australian governments might find the Pukpuk Treaty a difficult instrument to navigate if these “small wars” return. The Bougainville conflict gave rise to instability in Port Moresby and on more than one occasion the risk of a military coup. Then, the deepest nightmare of the ADF was being ordered to stabilise Port Moresby by facing down a mutinous PNGDF or police force.

None of this is to say the Pukpuk Treaty should not proceed but the Australian government needs a sharper focus on what a treaty may really entail. The Albanese government does not yet understand the full costs and consequences of what it is trying to do in the region. That starts with a deeply contradictory view of China.

The government knows it’s in a dire strategic competition with Beijing for influence in the Pacific but can’t bring itself to tell the Australian public the true nature of the Chinese threat. Albanese remains determined to publicly claim he has stabilised relations with China. The reality is that Beijing is trying to weaken Australia’s alliance with the US and reduce our diplomatic standing in the region.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was welcomed to Vanuatu with an honour guard earlier this month. The government should articulate a clear statement of the need to strategically deny Beijing’s influence in PNG, Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. Picture: PMO

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was welcomed to Vanuatu with an honour guard earlier this month. The government should articulate a clear statement of the need to strategically deny Beijing’s influence in PNG, Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. Picture: PMO

Part of the problem is a lacklustre foreign policy establishment incapable of thinking strategically and lacking the grit to deal with Beijing’s sabotage tactics.

Marles has foreshadowed that there will be a new defence policy statement in 2026. That creates an opportunity to put some coherence around too many piecemeal defence equipment and military diplomacy initiatives.

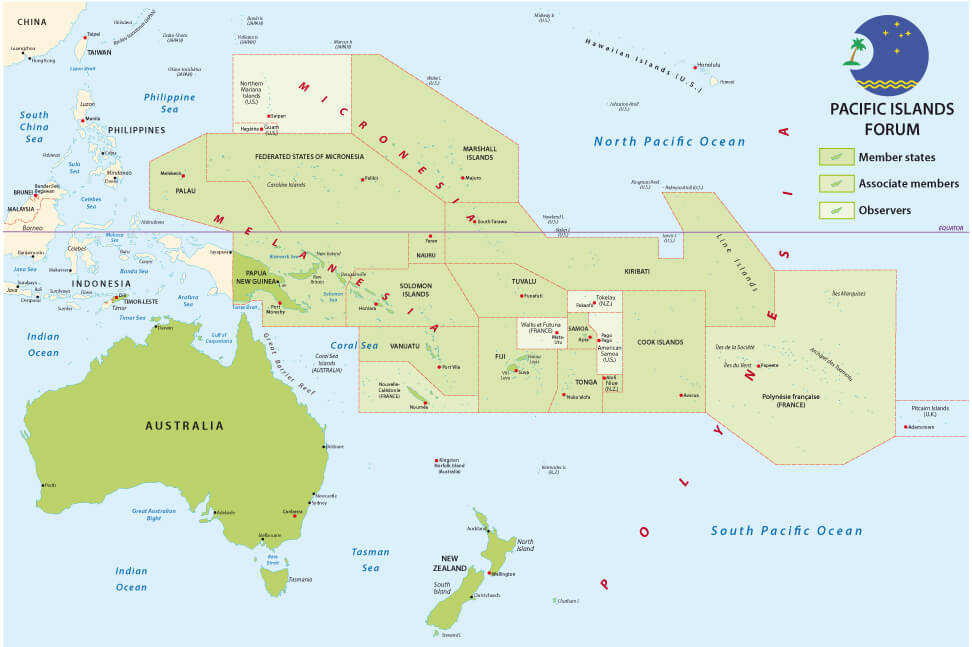

The government should articulate a clear statement of the need to strategically deny Beijing’s influence in PNG, Vanuatu and Solomon Islands; that is, the Melanesian states closest to Australia. We cannot allow this area to be dominated by a potentially hostile power.

The Pukpuk Treaty could be part of that strategy, but if the government can’t explain the policy clearly to Australians, what hope do we have to persuade our Pacific Islands neighbours to be part of this defensive project? Until Canberra is prepared to match words with sustained defence commitments, Beijing will continue to outpace us in the Pacific.

This article originally appeared in the Weekend Australian of 20-21 September 2025.