The Defence portfolio’s mid-year budget update, the Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements (PAES), has dropped and will be discussed at upcoming Senate estimates hearings. The PAES is meant to disclose any changes to the funding picture since the Portfolio Budget Statements published in March 2025 and give a sense of how agencies are tracking against delivery. There’s actually a lot to discuss this time round; there have been some pretty big muscle movements in the Defence budget, some good, some, well, not so good.

ADF workforce: finally some good news

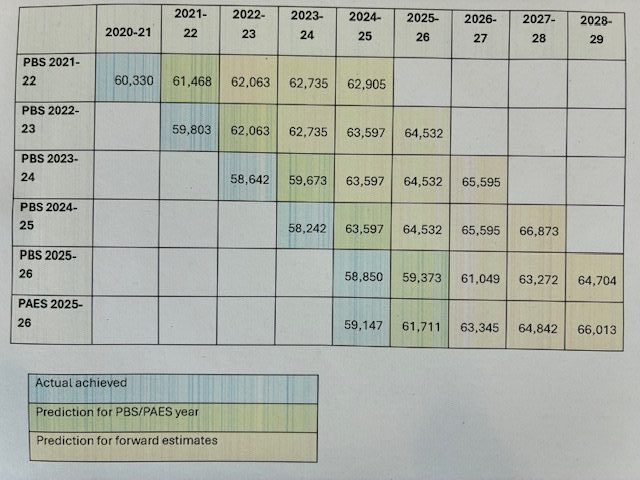

We’ll get to the money a little later, but first, some undeniably good news—the Australian Defence Force is finally making some clear progress towards its workforce targets (Table 13 on page 23 of the 2025-26 PAES). Readers will likely be aware that over the past decade, the ADF as a whole has made virtually no progress towards the growth targets set by the 2016 White Paper and 2020 Defence Strategic Review (although the picture is somewhat different between the three services).

The targets continued to grow every year while actual personnel numbers stagnated. The gulf between ambition and reality had reached 5,000 personnel by the end of last financial year, so the Government agreed to reset the target, dropping it from 64,532 to 59,373 for 2025-26 in last March’s Portfolio Budget Statements, with subsequent reductions over the rest of the forward estimates out to 2028-29.

Table 1: ADF personnel numbers: plans versus achievements

Note: Read across lines to see the predictions/targets set out in a particular year’s budget papers. Read down columns to see how the target for a particular year changed over time. Blue gives the actual achievement for a year.

The good news is that according the PAES’s prediction, the ADF will achieve and easily surpass the new target by 2,338 personnel, reaching 61,711 this financial year. Sure, one might say it’s progress against a reduced target, but putting targets aside, that number would still represent growth of over 2,500 compared to where the ADF ended last year. That’s easily the largest annual growth since the 2016 White Paper.

Another piece of good news is that all three services are doing well. The Air Force has pretty much been on target since the White Paper and so its target was barely reset. If it reaches the PAES prediction it will actually be around 650 people above its target. The Navy generally hasn’t been too far off its targets, so it was only reset by 240. Should it hit the PAES prediction, it will be around 400 over.

The problem child has been the Army, which had fallen to around 3,600 short of its old target. The target was reduced by around 3,700 to 27,773 in the March budget and the Army will easily pass that according to the PAES prediction, reaching 29,056. Again, while it may not sound like much of an achievement to surpass a reduced target, hitting the PAES number would represent annual growth of around 1,000 personnel, the best achievement of the past decade.

Of course, the PAES numbers are predictions not actual outcomes, and having the right total number of people doesn’t mean you have the right mix of individuals, skills and experience, but it does seem things are heading in the right direction. There is still a long way to go; the 2024 National Defence Strategy reminded us that the former Government set an ADF personnel goal of 69,000 by 2030 and almost 80,000 by 2040. The plan now is “the permanent ADF will grow to approximately 69,000 by the early 2030s” – some wriggle room there. There is no longer term figure like the 80,000 number given but it’s likely to be similar since the planned force structure set out in the 2024 Integrated Investment Plan is broadly similar to the 2020 one (albeit with a few capabilities tossed out), so Defence needs to keep up the good work.

It may be somewhat churlish to ask why it took Defence 10 years to discover the secret sauce of recruitment and retention. Part of the answer might be the $40,000 cash prize for people agreeing to stay for three more years. Perhaps we should just acknowledge the positive precedent set this year that shows it is possible to grow the AD—and keep our fingers crossed that it can find another 8,000 people in the short term and 18,000 in the longer term.

Incidentally, if you have more people, you have to pay them; Defence’s workforce bill has grown by $400.4 million in the PAES compared to the PBS, growing to $17,571.3 billion in 2025-26. Missing its personnel target has been a pressure valve for the Defence budget in recent years; continued recruitment and retention success will close off that valve.

The top line budget picture – watch my left hand, not my right….

We’ll move on to an area where the news is more mixed, the top line budget. The best place to see the changes to the budget are in Table 6: Variation to Defence Funding on page 16 of the PAES (noting this table only covers the Department of Defence, not the entire portfolio). At first blush things look very good. The table’s notes state that $2.0 billion has been re-profiled from 2027-28 to 2025-26 ‘to support increased preparedness and capability acquisition’ and $1.2 billion re-profiled from 2027-28 and 2028-29 to 2025-26 and 2026-27 ‘for the Nuclear-Powered Submarine Program.’

A little bit has been moved out of the Department to cover the latest addition to the portfolio, the brand new Australian Naval Nuclear Power Safety Regulator (ANNPSR). But the net result should be an additional $3.1 billion going into capability in the next two years, with the bulk of it ($2,457.3 million) right up front in 2025-26.

Numerous commentators, including SAA, have noted that while the Albanese Government’s 2024 National Defence Strategy increased the defence funding line it inherited from its predecessor in the longer term, it has provided painfully little new funding in the early years when, arguably, it is most needed. For example, 2025-26’s funding was only increased by $770 million over the funding for that year set out in the Coalition’s 2016 White Paper a decade earlier, a mere 1.3% increase. Hardly the act of a government wanting to put its money where its mouth is in ‘the most uncertain strategic environment since World War II.’ The PAES’s re-profiling finally breaks out of this pattern, with nearly $2.5 billion moved right to the front end in 2025-26. That’s good.

But, and this is a big but, the picture over the rest of the forward estimates is not so rosy. According to Table 6, 2027-28 has a net decrease of $2,867.7 million and 2028-29 a net decrease of $1,875.0 million. Certainly, a big decrease is to be expected in those years as some of their funding is brought forward. But there’s more going on. The total impact on the forward estimates is actually a decrease of $2,677.1 million compared to the March PBS picture. That’s right—despite the Government’s rhetoric around stepping up and historic funding increases, Defence has actually lost money in the PAES compared to the March PBS.

Where has it gone? The first place isn’t anything to worry about. With the Aussie dollar recovering slightly against the greenback, there’s been a foreign exchange adjustment with Defence having to hand back $781.6 million under the no win, no loss principles that ensure it retains constant buying power regardless of exchange rate fluctuations. Considering it picked up $3.3 billion in the March PBS after the Aussie dollar tanked, it’s not being hard done by.

That gets the decrease down to around $1.9 billion. Another $220.4 million goes to the ANNPSR. It may be leaving the Department but its still within the portfolio so its not a net loss and was presumably accounted for in the additional funding tipped into Defence by the National Defence Strategy to cover the SSN program.

Also leaving the Department is $44.5 million to cover the Defence and Veterans’ Services Commission and $78.0 million for the Agency for Veteran and Family Wellbeing.

But the big reduction—$1,557.9 million over the forward estimates—is ‘Savings from External Labour and Oher Non-Wage Expenses’, or put in other words, Defence’s contribution to consolidated revenue from savings achieved (hopefully) by replacing contractors with less expensive public servants.

Defence has largely been spared giving up significant efficiency dividends until now but it’s a strange time to start imposing them, with the Trump administration badgering its allies (I use the term loosely in light of the administration’s treatment of the countries formerly known as US allies) to do more and spend 3.5% of GDP on defence. Harvesting $1.5 billion from the Defence portfolio at a time of unprecedented strategic uncertainty seems hard to justify at a time when budgets are being squeezed across the Defence portfolio. But it probably makes sense over at the Treasury where making some savings to ballooning government spending looks good.

Unlike the PBS, the PAES doesn’t provide a consolidated portfolio funding line (i.e., the Department, ASD, ASA and ANNPSR combined) over the forward estimates, but we’ve done that for you and set out the changes to the top line in Table 1.

Table 2: Changes to consolidated Defence portfolio funding line

| 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | FE’s | |

| PBS 2025-26 | 58,989 | 61,848 | 67,631 | 74,143 | 262,610 |

| PAES 2025-26 | 60,886 | 61,893 | 64,937 | 72,294 | 260,009 |

| Delta | 1,897 | 45 | -2,694 | -1,850 | -2,602 |

Again, we can see the increase in 2025-26 along with the overall reduction in spending over the forward estimates compared to the plan set out in the PBS 2025-26 in March. The total decrease across the portfolio of $2.6 billion. In some ways, this is an even worse picture than the one set out in PAES Table 6: Variation to Defence funding which shows the impact only on the Defence Department’s bottom line; in Table 2 here movements between agencies within the Defence portfolio do not count as a loss as they are retained within the portfolio. So none of the $2.6 billion reduction is an artefact of movements between agencies in the portfolio: it’s all an actual decrease in the Defence portfolio’s funding.

The reprofiling and reductions inevitably have an impact on defence spending as a percentage of GDP as set out in Table 3.

Table 3: Changes to the Defence budget as a percentage of GDP

| 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | |

| PBS 2025-26 | 2.05% | 2.07% | 2.15% | 2.23% |

| PAES 2025-26 | 2.08% | 2.05% | 2.05% | 2.17% |

2025-26 gets a slight boost over the March PBS plan, but the remaining years all fall. Since we can’t see beyond forward estimates, we can’t tell if the Government is still committed to its NDS goal of hitting 2.33% by the end of the financial decade (i.e., 2033-34). What we can say is that the Defence budget has hovered between 1.9% and 2.1% of GDP since 2017-18; in March’s PBS it was finally meant to break out of this band in 2027-28 but passing that milestone has once again moved further into the future.

Clearly the Albanese government is unmoved by the US National Defense Strategy’s appeal for allies to do more or indeed by its own assessment of the strategic environment. Or they are hiding a “big reveal” for this year’s budget night and the release of the new version of the Government’s National Defence Strategy? If that’s the plan, this set of cuts in the PAES is an odd move.

Key changes in budget lines—SSNs

That’s the top level change. The next question is, what are the individual programs and projects that are getting that sugar hit in 2025-26? Considering the PAES refers to a $2 billion capability increase in 2025-26 and a $1.2 submarine funding increase across 2025-26 and 2026-27, there should be some clear signs of where it’s gone. But as always, it’s hard—and getting harder—to know from the budget documents. The PBS and PAES are accounting documents written by accountants for accountants to meet an accounting standard—they aren’t budget in the way that ‘regular’ people define it, namely a line by line breakdown of planned spending. Moreover you can get a different picture depending on where you look. Take for example the nuclear-powered submarine program.

If we examine SSNs as an enterprise, there are three main elements: the ASA, which has its own section in the PBS/PAES, Defence’s Program 2.16 (which is essentially contains the funds that the ASA is spending to develop an SSN capability), and now the new regulator, the ANNPSR. If we add those programs up and compare the PBS picture with the PAES picture, it looks like Table 4.

Table 4: SSN enterprise funding over the forward estimates (ASA, Program 2.16 & ANNPSR)

| 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | FE’s total | |

| 2025-26 PBS | 3,508.9 | 1,846.8 | 5,331.7 | 6,661.2 | 17,348.6 |

| 2025-26 PAES | 3,783.1 | 2,575.5 | 3,705.3 | 4,283.6 | 14,347.5 |

| Delta | 274.2 | 728.7 | -1,626.4 | -2,377.6 | -3,001.1 |

When we compare the PBS with the PAES picture we can see a moderate increase this financial year of $274.2 million followed by a large increase next year of $728.7 million. Those figures combine to make about $1 billion—not exactly the $1.2 billion mentioned in the PAES’s variations table but in the ballpark.

Interestingly there are big decreases in planned spending in the following two years that combine to a $4 billion downward adjustment. There’s no explanation for this decrease—are plans to build the shipyard and maintenance facilities not maturing as planned? We might recall that the ASA’s public documents claim it will start building SSN-AUKUS ‘this decade’, but planned spending 2028-29 is falling, right when we are apparently planning to start construction—so does that ambition still hold? There is, regretfully, no explanation and consequently no transparency.

When we shift the lens a little and look at SSNs as a project—the somewhat ominously named DEF 1, we can find information in the Top 30 acquisition projects table—but only for the budget year, not the whole of the forward estimates. Comparing the PBS and PAES gives us this information about the change in forecast expenditure for the 2025-26 financial year:

Table 5: DEF 1 (Nuclear-powered submarines) planned expenditure, 2025-26

| Military Equipment Acquisition | Other Project Inputs to Capability | Total | |

| 2025-26 PBS | 2,684 | 642 | 3,326 |

| 2025-26 PAES | 3,463 | 466 | 3,929 |

| Delta | 778 | -176 | 602 |

We can see that planned expenditure for DEF 1 has increased by $602 million to almost $4 billion. And we are still 6-7 years out from receiving our first SSN under the most optimistic scenarios. Incidentally that $602 million increase is rather different from the $274.2 million increase revealed in our enterprise view above. Why the difference? And which is the better way to understand the cost of our SSN program?

Key changes in budget lines—capability

As discussed above, the PAES’s variations table refers to a reprofiling of $2.0 billion from 2027-28 to 2025-26 to ‘support increased preparedness and capability acquisition’. That’s a rather large chunk of change and one might think it would be easy to find what that is being spent on in the PAES. However, nothing is ever simple in the budget statements.

Here are three top-level signposts:

- As noted above, personnel costs have risen by $400 million compared to the PBS, presumably because of Defence’s commendable achievement in this area, that now adds a budget pressure.

- PAES Table 9: Capability Acquisition Program shows a $1,422.0 million increase, with the bulk of that ($1,110.1 million) in the Military Equipment Acquisition Program.

- PAES Table 10: Capability Sustainment Program shows a moderate increase of $96.5 million over the PBS.

Taken together, that gets us to $1,918.5 million, in the ballpark of our mysterious $2 billion. But digging down further produces more confusion than insight.

Let’s take the Top 30 acquisition projects table (PAES Table 64). One might expect to see big increases in their 2025-26 expenditure, but with the exception of DEF 1 discussed above (whose $602 million increase is presumably covered by the $1.2 billion reprofiling for SSNs rather than the generic $2.0 billion reprofiling for capability), there are few spending increases to be seen. In fact, 22 of the Top 30 projects are actually spending less than their PBS estimate. Indeed the ‘gross plan’ for both the Top 30 and for the total approved projects (which includes the projects that are too small to make the Top 30) has decreased in the PAES.

The gross plan is essentially what project managers think they will spend in the financial year. However, Defence is well aware of the conspiracy of optimism and applies an over-programming margin to account for the inevitable gap between plans and reality. In the 2025-26 PBS it was a margin of $4,469 million against a gross plan of $18,443 million, or 24.2%. That’s a pretty pessimistic view, essentially predicting Defence’s project managers will only manage to move 75% of their planned expenditure.

In the PAES, things are more optimistic. The gross plan has decreased a little to $18,166 million, but the anticipated over-programming has decreased a lot to $2,918 million, or 16.1%. Regardless of whether you describe this as Defence’s anticipated performance has improved or its underperformance will be less bad, the upshot is that Defence’s projects will need $1,550 million more according to this forecast. When we take all changes in the Military Equipment Program into account, it’s spending $1,274 million more than the PBS picture. That could account for a big chunk of the mystery $2.0 billion. But as for what actual things the taxpayer gets for that, who knows?

So there we have it. Despite the PAES’s 232 pages, we can’t really say what Defence is doing with an extra $2.0 billion for capability this year. We can, however, say that Defence is spending a lot more on its SSN program than it had planned. Get used to hearing that line.

And if Deputy Prime/Defence Minister Richard Marles has convinced the Prime Minister and Treasurer Jim Chalmers to increase the top line Defence budget anywhere near 3% of GDP anytime soon, then the cuts to future years’ funding in this PAES document will make that a very big surprise for everyone.