Japan’s Mogami class frigate bid has beaten the German alternative to win the Australian Navy’s general purpose frigate project, which has a budget over the ten years covered in Defence’s investment plan of some $10 billion (with more required beyond that to deliver all 11 ships).

Under the Japanese proposal, our navy is almost certain to get its first Mogami frigate in 2029, because Japan has offered to give us one of the ships being built for its own navy.

That’s a unique thing that doesn’t just guarantee early delivery to our Navy: it highlights the fact that for Japan, this isn’t just about winning a warship contract, it’s about building a working strategic defence industrial partnership with Australia.

The decision announced by Deputy Prime Minister, Richard Marles (who is also still the Defence minister) is novel in the world of Australian defence— because it has been made without the usual byzantine bureaucracy and delay that has plagued getting new weapons into the hands of our military.

As an example, it’s taking Defence and the UK’s BAE 16 years to deliver the first of 6 Hunter frigates into naval service, and each Hunter is costing $9 billion. That looks like the price of 4 or 5 Mogamis for each Hunter frigate.

We can’t yet know the contractual price that’s still to be negotiated between the Defence department and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries for the program. But Mitsubishi has been building the original, smaller version of the Mogami frigates for under $A750 million each (figure updated for inflation to today’s dollars) since 2018, less for the later ships as build efficiency increased.

The larger upgraded Mogami with a 32 cell VLS will cost more, but is unlikely to be double that cost – at least while built in Japan. Even if these cost estimates do not include broader program costs, being able to buy multiple Mogamis for each Hunter underscores how odd persisting with the Hunter program is – with this perplexity added to by the fact that the Mogami is designed as a capable anti-submarine vessel, the special niche to be occupied by the Hunters.

It’s hard to see the value proposition for continuing with the Hunter frigate program with this comparative capability being available in greater numbers, much faster and for a fraction of the costs. If the Hunters were armed appropriately for a vessel of their size and were not so outrageously expensive per ship, then there could be some logic to not cancelling the program.

To see hope in the Mogami decision, though, perhaps it’s a sign that things are changing in how the $59 billion annual Defence budget is spent.

And the Mogami design is an impressive one in service with the Japanese navy, with an improved version being built for themselves and now for Australia. Its 32 missile cell magazine gives the new version double the missile capacity of the German bid and it takes 90 crew to run, about half the crew size of more traditional designs.

The price tag and the crew number is a result of the basic concept for the vessels, with Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Force emphasising that the Mogami-class is the first JMSDF vessel ‘aimed at saving manpower and reducing ship construction costs, taking into consideration the JMSDF’s manpower shortage and Japan’s tight finances being caused by the declining birthrate and aging population.’

If our defence bureaucrats can stay out of Japan’s way, the first three ships will turn up on time and on budget. They’ll be built in Mitsubishi Heavy Industries’ home yards which are pumping out two of these ships a year.

This partnership is one with the Japanese Government as much as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, with the potential for Japan to become a key alternative supplier for Australia of everything from missiles, ships, sensors and almost everything else across a modern military’s inventories. That’s a critical thing to pursue, given the US defence sector’s struggles to meet the American military’s own needs, let along supply partners reliably in conflict.

Now for the bad news – the risks Australia brings to itself and Japan

The big risks are all Australian – particularly transferring construction of later ships to Henderson WA. Henderson is meant to have an AUKUS submarine maintenance facility built there along with other new facilities, but the plans aren’t moving anywhere near as fast as this frigate project. A rebuilt Henderson Maritime Precinct has been promised by Defence for a long time now. It was outlined in the 2017 Naval Shipbuilding Plan, with nothing much happening as a result, and announced again in the 2024 Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Plan, with Richard Marles committing to a ‘consolidated Commonwealth-owned precinct’ there.

Any practical work to create new facilities in the precinct seems to now depend on the outcomes of an initial $127m set of planning, consultations, preliminary design and feasibility studies, along with ‘enabling works’ announced in October last year by Defence. These initial studies are going to continue into 2027, according to Defence.

The Henderson site is a complex web of corporate-owned facilities and land along with Commonwealth and State government interests and holdings. And of course, local government gets a say in developments. Henderson facilities are also used for commercial purposes – whether that’s shipbuilding or production of items for the offshore oil and gas industry, for example, and those users and interests aren’t just disappearing.

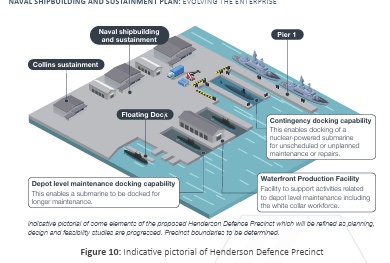

On top of these overlapping and not always aligned interests about who gets to do what, when, at Henderson, the AUKUS plan for the precinct now includes building a contingency docking capability and supporting infrastructure and facilities for nuclear-powered submarines, along with facilities for depot-level maintenance of nuclear-powered submarines. Building anything to the standards required for nuclear safety is something new to anyone in Australia except for folk involved in the Lucas Heights research reactor, so the timeframes and costs will be a journey of discovery.

An artist’s impression of what the Henderson precinct might look like, subject to conceptual work & feasibility studies. Image: Defence

The Japanese Government and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries will be watching whether these planning efforts are resulting in any certainty for what they need to plan and deliver to allow frigates 4 to 11 to be built in Australia. The worst case for MHI is that sometime in 2030-2034 when they want to start building warships 4 to 11 in Australia, Henderson itself is a major construction site.

Right now, Civmec’s large sheds look the most likely place for a frigate build in the West, and Civmec has signalled it’s staying in naval construction by buying out Lurssen, its partner in the troubled OPV program recently for $20 million.

It’s Austal, not Civmec, though, that has just been appointed as the Commonwealth Government’s strategic shipbuilding partner and it’s Austal that has a big future order book of construction programs for Defence – notably medium and heavy landing craft and Evolved Cape Class patrol boats. That appointment was announced on the same day as the general purpose frigate decision. Interestingly, neither the Mogami decision nor the Strategic agreement with Austal referred to the other decision. The agreement with Austal does talk about Tier 2 vessels, though, a label used to describe the general purpose frigates. So there’s a strong implication that Austal will be MHI’s build partner. However, Mitsubishi, Austal and Civmec can’t plan and invest on implications and possibilities.

All this means that the commercial interests, equities and negotiations to make an Australian build of the general purpose frigates a reality are another puzzle yet to be worked through – and time is getting short.

One thing that the Commonwealth Government could do to shorten timelines and get construction moving in Henderson would be to appoint a ‘Henderson Precinct czar’ with the agreement of the Western Australian government and the local government entity (the City of Kwinana) with interests in Henderson. Vesting Commonwealth, State and local government authority in an empowered individual, and providing the resources – financial and human – required to make the new Henderson precinct more than paperwork by 2030 would not just signal commitment to AUKUS. It would also help our Navy and the companies who are building it deliver what our nation’s security needs years faster than leaving things to the stately, complicated inter-government negotiations and processes we’re seeing to date.

Failure gave birth to the general purpose frigate program

It’s worth remembering why the general purpose frigate program is required: because the ‘continuous naval shipbuilding’ program announced in 2017, and committed to by both ruling parties when they have been in power since, has failed to deliver more than a single almost unarmed Arafura Class patrol vessel to the Royal Australian Navy in 8 years. The ‘plan’ was destined to see the RAN’s surface combatant fleet collapse as the aged and fragile ANZAC class frigates are withdrawn (something that has already begun). But the Defence Department’s design from that time bumbles along, prioritising small numbers of industrial jobs over equipping our Navy in a timely fashion.

So, the speed of decision making with this particular frigate program, and the ability of MHI to then deliver ships to our Navy is refreshing but also necessary. And the decision opens up larger opportunities in the Japan-Australia strategic relationship, like a formal ANZUS-style Aust-Japan security treaty, as my SAA colleague, Peter Jennings has set out.

Let’s celebrate this win for Australian security and our strategic partnership with Japan – and hope that Canberra can move as fast as the Japanese shipbuilders will.